Michael

Atiyah (centre) and I.M. Singer (left) receiving the Abel Prize in 2004

courtesy Scanpix/The Norwegian Academy of Sciences and Letters

Michael

Atiyah was a distinguished mathematician with a stellar scientific

career spanning over 60 years. He passed away on January 11 aged 89. He

received the Fields Medal in 1966 and the Abel Prize in 2004, and is

best known for his work with Isadore M. Singer on the Atiyah-Singer

index theorem.

In October 2016, Atiyah spoke to C.S. Aravinda, the chief editor

of Bhāvanā, a journal of mathematics, at the former’s home in Edinburgh.

The interview is presented in full, and has been lightly edited

for clarity. Aravinda’s words are in bold and Atiyah’s are plain.

§

I am delighted to meet you. Which part of India are you from?

I am from Bangalore, which is in the southern part of India.

I have visited Bangalore several times. In fact, I have even planted a

tree in Bangalore. There was a chap there at the Raman Research

Institute who was a friend of mine, called S. [Sivaramakrishna]

Chandrasekhar – not the astronomer. He worked on liquid crystals. He

said he was also a nephew of C.V. Raman. They are all related.

Many years ago I was reading a paper of C.V. Raman. I think I was

most impressed by a statement saying something like, “It is from my

collection of diamonds, I have discovered the following facts.” [

Laughs] Do you know other scientists who say “I have diamonds”? He was a rich man and had a big diamond collection.

You also have other Indian connections. I noticed that, in

1966, the year you were awarded the Fields Medal, the Indian

mathematician Harish-Chandra gave a plenary talk at that conference.

Yes, he gave a plenary talk there. When I was a graduate student in

Cambridge, I went to Amsterdam in 1954 and he gave a plenary address

there too. I remember a very clear impression that I had, which was that

he spoke English much faster than any Englishman. In English, you have

ups and downs. But he was like a machine gun, he spoke much faster. He

spoke beautiful English. Of course I couldn’t understand anything. It

was not the English I could not understand. I was a graduate student and

he was professor or something and he was talking about advanced work. I

was just finishing my PhD.

You were finishing your PhD at that time?

I finished my Ph.D. in 1955. But I was just beginning my career, and

he was several years older than me. He was smartly dressed. Yes, I

remember very clearly that first meeting. Of course, later on we met as

colleagues. I visited Princeton, but then he was in Columbia at the

time.

I think you visited Princeton in 1955-1956. But he visited Princeton again in 1956-1957, a year after you left.

Actually, I was still there for the fall term in 1956. Of course he

became professor later on. I went to Princeton for seminars. I was

certainly there in… oh dear… [

laughs]

Atiyah (centre) receiving the Fields Medal at the 1966 ICM in Moscow. Credit: Michael Atiyah

I think you went there sometime in 1969. Because Nigel

Hitchin mentions in some place that soon after he finished his PhD, he

went with you to Princeton.

He came as my assistant. That was a good time. Anyway, later on there was another Indian who came to work with me – Patodi.

Vijay Kumar Patodi, yes. I was going to ask you about him too.

Very brilliant man. And a very sad case. He died almost at the same age as Ramanujan.

Around the same age, in his early 30s, yes. He died of renal failure.

His case was more complicated. Anyway, at that time my interests were

not very close to Harish-Chandra’s. My interests became closer much

later, possibly after he died. When did he die?

He died in 1983, at the stroke of his 60th birthday.

I know that. He was going to have an operation but he couldn’t have

it. So we didn’t really interact much. But I got interested in that kind

of mathematics probably after he died, 30 years ago.

I have read somewhere that he was going to give a talk

somewhere in England, I don’t remember where. And then he had a heart

attack and cancelled his visit.

Yes, in 1982. At that time, I was back in Oxford. There, I had a

succession of Indian visitors who came to work with me, mainly from

Bombay who were students of M.S. Narasimhan. A whole succession of them.

I got to know S. Ramanan very well, a very nice man. T.R. Ramadas came a

little later. They all came to work with me in Oxford in that period.

Yeah, it was quite a strong Indian connection. Long time ago.

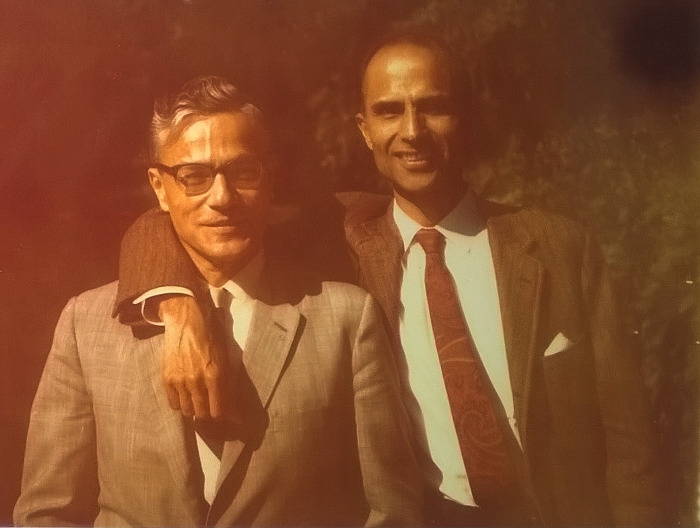

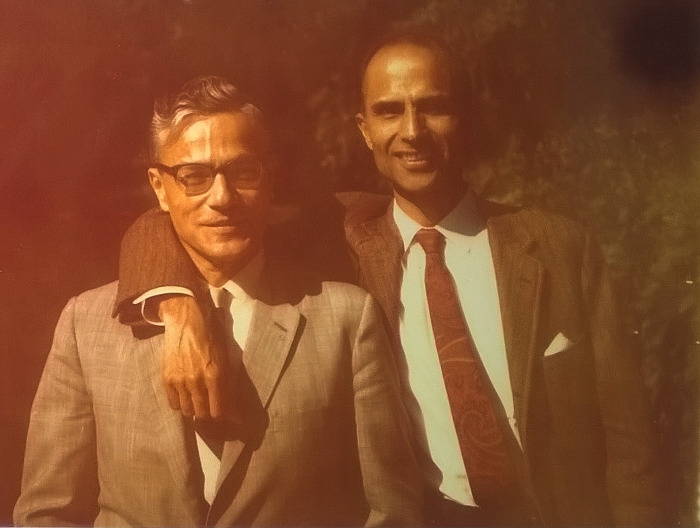

Armand Borel and Harish-Chandra. Credit: Suresh Chandra

So you first heard Harish-Chandra at that Amsterdam

conference in 1954. When you were at the Institute for Advanced Study

(IAS) in Princeton later, was there any interaction?

I was at IAS as faculty from 1969 to 1972, and Harish-Chandra was

already there. We were only about eight or nine colleagues and we had to

meet to discuss things. I got to know him from close. We got to know

each other’s families, as we all lived quite close together. For

instance, their daughter Premi married Pierce, who was a fellow at

Trinity College, Cambridge.

But we didn’t really overlap much mathematically. Our mathematical

interests were a bit different. But I got to know him well. Both he and

his wife were very tall and upright. They were imposing Indians you

know, and I was short, but they were nice to us. They lived on Battle

Road. I also knew Armand Borel very well, and he was very friendly with

them. I think Harish-Chandra came from Allahabad and not from Bombay.

Originally, he was a physicist.

Correct, he did his PhD with Paul Dirac.

You know this story about Harish-Chandra and Freeman Dyson?

I do, but please tell us about it.

I think it’s a more or less true story. Harish-Chandra and Dyson were

both graduate students in Cambridge after the war. Harish-Chandra was

doing physics with Dirac and Dyson was doing number theory. While they

were walking down the streets, the story is that Harish-Chandra tells

Dyson, “Physics is in a mess and I am going into mathematics”. Dyson

said to him, “Physics is in a mess, and that’s why I am going to go into

physics.” And they switched over.

Of course, Dyson still kept an interest in mathematics.

Harish-Chandra used his knowledge of physics to direct his mathematics.

He worked on infinite-dimensional representations because of the work of

the Russian school led by Israel Gelfand. Harish-Chandra wanted to do

it more rigorously.

So Harish-Chandra and Dyson had this very odd connection. I got to

know both of them. I knew Dyson very well too; he is still very much

around and must be about 90 now.

Both Harish-Chandra and Dyson were born in the same year, 1923, and so Dyson must be about 93 now.

Exactly. More recently, at the Royal Society in London, as a

tradition, if you have been a fellow for 50 years, they give you a nice

little dinner for which you could invite your friends. To succeed in

this, you have to be a mathematician or physicist, you have to be

elected very young and you have to get very old. So not many people have

qualified [

laughs].

Right!

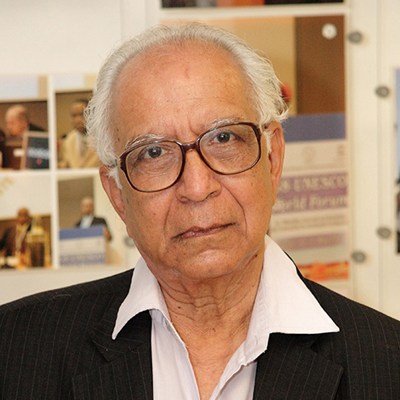

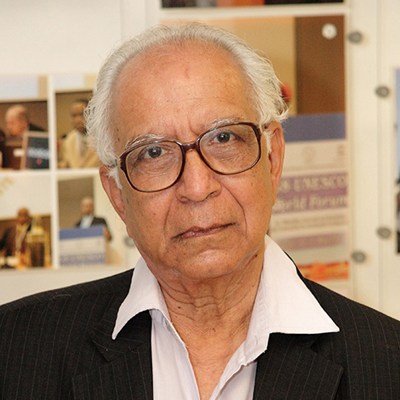

M.S. Narasimhan. Credit: ICTS

When I was President of the Royal Society, one person did qualify,

and that was Rudolf Peierls. He was involved with the atomic bomb. I had

to preside at his dinner, and we had Hans Bethe as his guest. After I

left the Royal Society, when I was getting to my fifty years [as a

fellow], I wrote to the Royal Society, more or less saying “I hope you

haven’t forgotten that there is a tradition.” And they wrote to me

saying “Oh, we’ve forgotten all about it. For the last ten years, we

haven’t had any. Oh dear, what are we going to do?” [

laughs].

So they said, “Ah, we’ll invite everybody who were elected in that ten

year period.” Only two people came – Dyson and me. I was elected for

fifty years, and he was elected for sixty years. None of the guys in

between were able to come, so it was rather funny. I have slight

disagreements with Freeman Dyson, but he is a strong minded person with

strong views.

Harish-Chandra and Dyson were both six years older than me. So when I

went as a graduate student to Amsterdam, I was 25 and Harish-Chandra

was 31. In terms of age, the difference was only six years, but in

mathematical terms it is the difference between a post-graduate and a

senior professor.

You came back to the UK from IAS in 1972. Why did you come back?

Well, when you make a decision, first of all, you don’t know why you’re making it! [

Laughs]

There can be many different causes. Even if you can easily list the

causes rationally, the decision is usually an emotional one. And you

don’t admit it. I can talk for hours but there are a few factors. One is

we had been in America for years and my wife was not very happy. She

had a better job in the UK than she had there. Also, we used to spend

half the time there and half the time back here, which was not very good

for her because she could not get a job properly. Plus my children were

growing up – the eldest one was 16 and if we had stayed for a few more

years, he would have gone to college in America and then we would never

be able to leave. So it was now or never.

And thirdly, I was at the institute when it was an unhappy time

between the director – at that time it was Carl Kaysen – and the

faculty, particularly the mathematicians, including André Weil. I was

caught in between and I felt very unhappy. It was a difficult decision,

as I liked the institute and it suited me very well mathematically. But I

felt that I was being selfish in putting myself first. My family comes

first. A job turned out for me here and I came back. It worked out very

well and I got lots of brilliant students. It was really a toss of a

coin, and my heart made the decision. It was not rational. Sometimes

your heart makes a better decision. [

Laughs]

Yes, I think so too. As you said, when your heart makes the decision, there is no reason why.

Precisely. It is very complicated. It’s an emotional response which has many factors.

I have been to the IAS as a visitor, a young man, an older man and

I’ve known all the people and all the directors very well. It is a funny

place. It can be marvellous and vibrant for the right person at the

right time. Its most useful function is that it is a place where young

people go for postdoctoral work. The school of mathematics was a big

one, and a large number of post-graduate people came there either for

postdoctoral work or on their first sabbaticals. They were all very

young and active and some of them, having been in the army, were delayed

by five years.

[This stage in one’s research career] is a very formative period.

Everybody is full of ideas. They go to seminars at the university, at

the Institute, and the faculty on the whole have very little contact,

with a few exceptions.

The Princeton University is also close by…

Of course; the university is fine but the institute was meant to be

separate, you see. And some people were very separate – they didn’t come

in at all, they didn’t mix with students. Sometimes, each person would

select assistants who were more or less right-hand men. Otherwise, all

of them were selected by competition and some faculty would attract more

students and used to work with them – and some did not. But it depended

mainly on personalities, and in some cases the areas of interests.

As a young visitor, I hardly knew the professors. Although, through

one or two lectures, I got to know some of them, like Dean Montgomery,

quite well.

Freeman Dyson. Credit: Jacob Appelbaum/Wikimedia Commons

Was Atle Selberg also there at that time?

Yes, he was there but he didn’t interact very much. I wasn’t doing

number theory very much. We didn’t interact with all the famous people

at all. On the other hand, they were the people – the flagships – that

brought the money in that would enable the young people to come. So they

were kind of the umbrella. But the interaction between the postdocs and

the faculty was very small. Some people interacted quite a lot. For

instance, Borel interacted quite a lot because of his wide interests.

He used come to India quite often because he loved Indian music.

When I first went to IAS, he wasn’t there. He came later.

All the faculty at IAS were very clever people obviously, but

sometimes there were odd and unusual personalities who didn’t get on

with the other faculty or the students, or had some kind of problems.

There was Selberg and Arne Beurling and they worked on their own to a

great extent. They were Scandinavians – they didn’t have much contact

with others. There was Marston Morse. He was retired but he was still

active when I was there. He had a few acolytes, I would say. And Hermann

Weyl was there before I arrived. He was a marvellous guy. He was a

really great man, especially with young people.

The physicists were even younger and more active. All the

mathematicians were slightly odd – not meaning they were bad but they

were unusual. Some of them had one or two people, assistants, in little

groups who were in their area. It was a very odd situation. Everyone

wanted to go to IAS because there were famous people.

Another person who was there was Kurt Gödel. I had heard the name a

little bit. He was a very odd person, extremely odd. He eventually died

of malnutrition.

I see…

Gödel was the greatest logician of the 20th century. For a long time

at the institute he wasn’t even a full professor. He was only a sort of a

half professor. And then he had paranoid ideas. He thought that people

were out to poison him. After his wife died, he starved to death. He

just didn’t feed himself; he was really an extreme case. I knew him

before that. So if somebody had serious psychological problems, the

institute was not a good place to be. There was too much pressure.

John von Neumann was an enormous personality. Both Hermann Weyl and

Einstein had died before I came. Their reputation still lives on.

Princeton was the place which had all these names – Einstein, Weyl, von

Neumann – who were great figures at the time. So you could chat with

great mathematicians and physicists.

I looked through the institute records for a while when I was there.

There was this talk by George Dyson, Freeman Dyson’s son. He had an odd

history – he ran away from school, lived in a treehouse. Then he came

back and became an author. He spent a year at the institute officially

at the invitation of the director, accessed all the archives, gave

talks. He was supposed to be writing a book. The title of the book was

‘Turing’s Cathedral’. It is about the history of computing.

A fairly recent book, yes.

It is really about von Neumann but he thought Alan Turing’s name

would attract more people. So it’s called ‘Turing’s Cathedral’.

Interesting book. I spoke to him when he was there, and he told me

stories such as, for example, that the institute tried very hard to get

Paul Dirac. They tried very hard to get Turing to stay; he had been

working with von Neumann. But he didn’t want to stay. So there were a

lot of successes and failures.

There were some people, like Carl Ludwig Siegel, who went back to

Germany after the war (1951). So they attracted people but sometimes

they lost them. But they tried very hard to get all the top people. They

paid big salaries but still some people had good reasons not to go, all

sorts of personal reasons.

As you said, sometimes it is a decision of the heart. Secondly, certain places suit certain personalities, I guess.

Of course. If you wanted peace and quiet at the institute, and you

wanted to get on with your work with one or two people to talk to, had a

good and stable enough family life, you liked the country, then it was a

marvellous place. So many of these things were good. But I had my

family worries about other problems, and eventually I left. The one

thing that I missed when I was there: I didn’t have graduate students. I

had one or two graduate students who were unofficial, a few of them who

were my assistants, and did their PhDs at the university. When I came

back to Oxford, I got a flood of good graduate students. All very

brilliant. I was very fortunate.

Yes, you have a large number of them.

Yes! Simon Donaldson was my student. Graeme Segal was my student. And

Patodi being a sort of a student. I liked having young people with me.

It worked out very well. I came back just at the time when I was well

known enough that people would come to work with me.

Since you mentioned Patodi: Perhaps you came to know about

Patodi through his paper? Or was it when he was in Princeton visiting

IAS?

I think I got to know him as a student of Narasimhan. What Patodi did

was that he gave some very clever proofs of some difficult theorems in

differential geometry. He developed his own formalism, which I couldn’t

understand. Raoul Bott couldn’t understand it. We knew the results were

interesting. So then, through Narasimhan, we invited him to come, and he

spent two years at the institute in Princeton. Bott, he and I worked

very closely together and we understood what he was doing.

Interestingly enough, subsequently, when the work we were doing got

to physicists, the physicists rediscovered what Patodi had been doing in

the language of supersymmetries. But we were there first. They gave,

subsequently, a physicists’ proofs of what Singer and I were doing, but

Patodi did it first. I don’t think they really gave him proper credit.

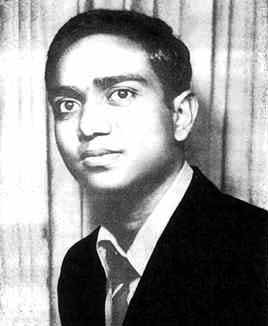

He did it, he found it all by his hand. He was a bit like Ramanujan.

Yes, you mention that in your preface to the collected works of Patodi.1

He had a kind of intuitive feel for formulas and he couldn’t explain

how he got them. And he was very clever. We struggled very hard to

understand them. And through that we learnt from him and we published

papers. He had very good insight.

But you see, like Ramanujan, he had extremely rigid habits of eating.

He was a Jain. He had to go wash his hands before doing anything. He

had to cook his own food. When Ramanujan came to England, he was

somewhat similar. He was very fussy about the food. He was cooking on

his own and he actually had malnutrition. He couldn’t get the vegetables

that he needed.

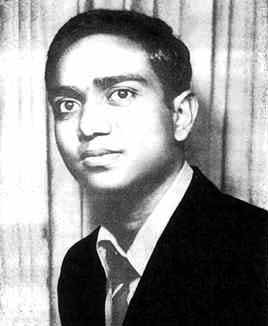

V.K. Patodi. Source: Author provided

And there was also the war at that time.

Of course, that didn’t help him any.

In Patodi’s case, it may have been even more rigid, because observant Jains eat before dark.

Exactly. Very rigid. He also had a lot of serious illnesses, which he

didn’t take seriously enough. He discovered he had kidney failure and

also tuberculosis.

I see. I didn’t know he had tuberculosis.

I think so. But he certainly had more than kidney failure. When I got

back to Oxford, we heard from people in India that he had kidney

failure, which is a serious illness, and he needed a kidney transplant,

which costs a lot of money. I contacted a friend of mine who was a

surgeon and an expert at [treating] kidneys and asked him if he would

consider helping. And I said, well, it costs a lot of money and I and my

friends will try to get some money together to pay for it. He said he

wanted to see his medical papers, so we arranged for it to be sent to

him.

And when he got them, he told me that it was much more serious than I

thought. He had kidney failure but also lots of other problems as well.

This meant it would be a very delicate operation. I then found out that

it wasn’t just kidney failure but that there was something more, so his

case was very difficult. Still, we were discussing whether we should

bring him to Oxford and have the operation done. But then we heard that

there was an American expert who was visiting India who would consider

doing the case. Then the expert went there but I think Patodi died while

under anaesthetic before the operation.

He died tragically before the operation could be made because his

system was so weak. He died at the age of 31. He wasn’t quite in the

same league as Ramanujan but he was very good. So there are lot of

similarities. Ramanujan went to Cambridge to work with Hardy. Patodi

came to Princeton to work with Bott and me. We wrote a lot of papers

together. I learnt a lot from him, his intuition. He learnt something

from us. So here was a very parallel story. Ramanujan was probably

ahead. But nevertheless, it was a lot of similarity.

I’m very happy to see that Patodi’s name is accorded and recognised

now. Unlike with Hardy and Ramanujan, he was a very emotional part of my

own life. I had got myself tied up because he was such a nice man. I

think he was an easier person. Ramanujan I think, was a difficult

person. Patodi was a very easy person, very nice person – a really

modest person; and you don’t find really modest people in the world –

and we didn’t have any problems. But his medical problems were more

serious and he had this very strict food regimen.

Raoul Bott (left) and Michael Atiyah. Credit: Bott Family

I don’t know if Patodi came with his wife.

Hang on. Was he married?

Yes. His wife’s name is Pushpa Patodi. Maybe he married after he went back to India.

He came as a young man, you see. When he came to work with me, he had

just done his PhD with Narasimhan. So he was probably only in his

middle twenties. I don’t think I remember his wife. He invited us for

dinner to his house once or twice and he did the cooking. You know, this

story of Ramanujan is somewhat similar but Ramanujan invited his guests

and walked out halfway through the dinner only because the guests

didn’t have a third helping.

When you talk about Raoul Bott, what I must definitely recall is that you wrote an obituary of his in Bulletin of the LMS,2 which I felt was very warm and had a lot of personal touch.

I put my heart into it. He died in 2005. He and I both got very

friendly with Patodi. We had lunches with him, and he used to cook us a

meal. But we learnt how fastidious he had to be about his food.

He was a vegetarian too.

Yes, that’s okay. You can be a vegetarian and eat a lot. First time

when I went to Mumbai, I was looked after by K. Chandrasekharan. He was a

vegetarian. He invited us for dinner and gave us a most enormous meal

to show us that vegetarians could eat very well and in large quantities!

[

Laughs]

So you think he would have, potentially, gone on to do very well.

Yes. Because he had a lot of insights and by the time we finished

working together, he had learnt a lot more things. He would have gone on

to be a very famous mathematician.

I was asking specially because you mentioned that later on physicists did the same thing.

Yes, he would have been able to fill that gap. There were not a lot

of people in that area. He might have been in any country in the world.

But probably because of his Indian connection, that he was a Jain, he

would have stayed in India. There are a lot of people now as it is very

popular. There is this physicist called Ashoke Sen – he is up there,

right? So there are now enough Indians who have gone back. After all, it

is 30 years now since that time; things have changed.

The advantage of living longer is that you get this panoramic view.

And you see things in different periods and in different times, the

influences of people, and you realise that what you read in the history

books is not the true story. True stories are much more complicated with

who influenced whom and how, and usually the history books are wrong [

laughs]. You know, they are always wrong. The further away you go, the more wrong they are.

It becomes speculation.

You know, it’s a bit like ordinary history. I am also interested in

history. They say that history is written by the winners. And then of

course people do research. They go back and say “Ah, this is all wrong.

He wasn’t the villain, this was the guy who was the villain!” England

history is full of it.

Mathematics is a subject where the establishment rules. People in

positions of power can influence somebody’s career. It can be for the

bad. And people don’t discover this for a long time, sometimes for

hundreds of years.

When you were growing up here, you were of an impressionable age when the war broke out in Europe.

Yes, but I wasn’t in Europe. I was in the Middle East.

Did the war affect you in any way?

Well, probably. My mother was from this country and my father was

Lebanese. He worked in Khartoum in Sudan, which is at the junction of

the White Nile and the Blue Nile. His family was in Lebanon, and my

uncle worked in Palestine at the time. We went to secondary school in

Cairo and in Alexandria.

When the war broke out, we were in England on holiday. My father had

to go back immediately, leaving my mother and children in England. We

then followed across through France, just before France collapsed, and

got to the Middle East. We spent the war entirely in the Middle East.

After the war, my father retired and came back to England.

Did it affect you academically?

Well, when I was young I went to this primary school in Khartoum,

which had only about 20 children of all ages because it was just for the

children of government officials. When I became 12 it was not good

enough, and then I was sent to the secondary school in Cairo. You see,

my father had been to a very famous school called Victoria College,

which educated many famous people. It was a British school in Egypt for

people like, for example, Omar Sharif: he was younger, a small boy, when

I was there, and the future King Hussein [bin Talal] of Jordan. So this

was the kind of people who went there [

laughs].

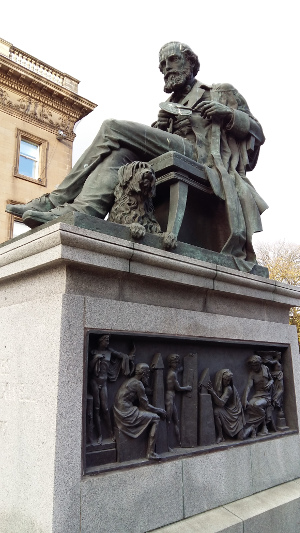

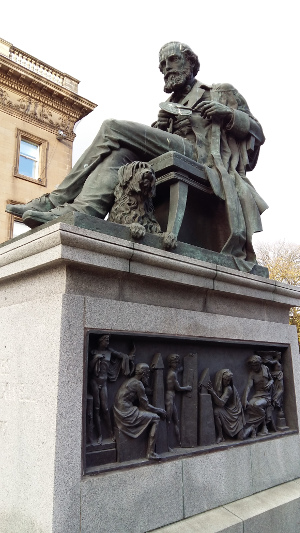

Statue of James Clerk Maxwell at St. Andrew’s Square, Edinburgh. Source: Author provided

It was a very good English school. My father went there before me. I

went there; I got a good education. But it affected me. English was my

native language. My mother spoke English, my father had been to Oxford.

My brother and I were both advanced for our age by the time we got into

this school, so they put us in a class which was two years older. I was

age 12 when I was with those of age 14 and finished the school when I

was 16. So I was always two years younger than everybody else. It had a

funny effect on me. If you weren’t careful you would get bullied by the

big boys.

So I usually had to have a big boy as a defender because I was helping with their homework [

laughs]. The deal was – well not really a deal – if you helped them with their homework, they would say “Don’t hit my friend!” [

Laughs].

So I got through very well there. But my brother was not so lucky. I

think he did get a bit bullied – he was younger still. When I was 16, we

left and as my father got a job in Britain, the whole family came back.

So we lived here after that.

Was there a teacher who inspired you? When did you realise that you were interested in mathematics?

The family folklore is that my father said that he knew I was going

to be a mathematician because every year when we travelled to the Middle

East, I always managed to exchange my pocket money at a good rate [

laughs]. That was his story anyway.

Good with calculations.

Yes, good with calculations. I don’t know, at school I was always

very good at mathematics. I think once I didn’t come on top in

mathematics and I was very cross. I was always expected to be top in

class in mathematics. But I liked other things, too. At one stage, I

wanted to be a chemist. But I discovered that chemistry was too much of

memorisation, you have to remember all the formulas. So mathematics was

much simpler, and I had quite a good mathematics teacher in Cairo. He

was also the sports teacher.

Do you remember his name by any chance?

Yes, his name was S.H. Griffiths. He was in charge of the cricket

team. I remember he was nicknamed Figaro. Figaro is a character in

The Marriage of Figaro.

The composition by Mozart.

Exactly, so the boys would call him “Figaro! Figaro!” The boys at the

school had these funny jokes. When I was in the last year of school, we

went back to Alexandria, which is where the school was originally but

had to move out as it was given to the army as a hospital. So then I had

a different teacher. He was tall, severe and unbending. But he had a

difficult life because his wife was in a [mental health] asylum and he

couldn’t get a divorce. So it was a sad life. He was a chemist but he

was a good mathematics teacher. He helped me to get on with mathematics

quite a bit in my last year and gave me advice.

When I was at Trinity College, we had a visit from the Indian

president at that time. We had to show him the books with all the names

of people who have been there. I remember showing him three famous

Indians who had been at Trinity College at different times. One was of

course Ramanujan, the second was Jawaharlal Nehru, and the third was the

most famous Ranjit Singh

ji, the cricketer! So there were these three great figures; Ranjit Singh

ji

was way back in 1870-1930, the only Indian to play cricket for England.

Then we had Nehru, a great figure in Indian history, and Ramanujan. We

had a sportsman, a mathematician and a politician, which is pretty good.

So we had a long Indian connection.

We also discovered later on that we had Mohammad Iqbal, who was a

great poet and philosopher of Pakistan. So we had both Nehru and Iqbal

in the same college. There were many others. Subrahmanyan Chandrasekhar

was there at Trinity and we also had Ernest Rutherford and other famous

physicists.

After you came to Cambridge you met William Hodge, who was

your thesis advisor. I will now bring our discussion closer to

Edinburgh, the place associated with James Clerk Maxwell.

Edinburgh is a great place culturally in Scotland. James Clerk

Maxwell was born in Edinburgh and went to the university there. Hodge

too was born in Edinburgh and went to school and university there.

Further back, Edinburgh had the great philosophers David Hume, Adam

Smith and Walter Scott.

Many people from Edinburgh went to Cambridge; Maxwell went to

Cambridge. In fact, my wife, who did her PhD in mathematics, went to

Edinburgh University and then came to Cambridge. It’s part of a strong

tradition. Basically, in the sciences, people [from Edinburgh] went to

Trinity College.

Did Maxwell’s equations of electromagnetism provide the main ideas behind Hodge’s theory of harmonic forms?

Yes. Hodge got a good training in Edinburgh. He learnt about

Maxwell’s equations. And then in the path of his understanding, he

combined that with differential geometry and algebraic geometry. That

was a very big step which people didn’t fully understand at the time.

Hodge was doing Riemannian geometry and Maxwell was doing relativity in

Minkowski space, not Riemannian space. That means that the equations in

physics are hyperbolic equations and in mathematics they are elliptic

equations. Algebraically they were the same and Hodge didn’t mind but

people thought they were very different.

Now, in the recent developments, these things are fused together once

again. In modern theory, they go very happily from the Lorentzian world

to the Riemannian world by Wick rotation. They change the sign. It is

standard practice now in the whole of physics. What Hodge did was very

far ahead of his time. Now we understand that Hodge and Maxwell are part

of a single school, the Edinburgh school.

Somehow it seems that it is tied up with your living in Edinburgh.

It is very much so. George Street in Edinburgh ends in a square at

each end. At one end, which is called St. Andrew’s Square, you will find

a statue of James Clerk Maxwell. I put that statue up. I found the

sculptor, raised the money and I persuaded the city council to put it

up. At the time, when I was President of the Royal Society of Edinburgh,

we put it up and we opened with a conference. It is an old style

statue. If you look at its front side, you will find Maxwell’s

equations.

Maxwell’s equations of electromagnetism, engraved below his statue in Edinburgh. Source: Author provided

You said that your interest in representation theory came

after Harish-Chandra died. You also met Hermann Weyl at IAS and admired

his works, of which finite-dimensional representations forms a major

part. So… you weren’t really looking at it then?

Atiyah: Let me backtrack a bit about Hermann Weyl. You might like to read the obituary to Hermann Weyl which I wrote.

3 You

will find it in an unusual place, which is for the US National Academy

of Sciences. It was written fifty years after he died. Usually the

obituary is written shortly after you die. The US Academy finally tried

to get people to write, but everybody who knew him had died by then. So

fifty years after they elected me, they wrote to me and asked, “Would

you like to write the obituary?”

I said fine and I wrote his obituary fifty years after he died.

Usually, if somebody dies, we say, “If we look over the next fifty

years, we will find out what influence he had.” I was able to say “Look

backwards.” So I wrote it retrospectively and I think you will like it.

It is a nice and short article. It shows the influence he had on all

subjects of mathematics. He died in 1955. Until my time, everything I

did – I always found that Hermann Weyl was the guy who did it first. He

was always there first. He was the kind of man who set the tone for the

development of mathematics in the subsequent fifty years. And

Harish-Chandra grew up in that period. That is one influence.

Hermann Weyl. CreditL Shelby White and Leon Levy Archives Center, IAS Princeton

The second influence was of course, in some sense – you could say

that what Harish-Chandra was doing was extending Hermann Weyl’s work

into quantum mechanics because his work was on infinite dimensions. The

first people who worked on this theory were people like Eugene Wigner

and Valentine Bargmann, and then subsequently Russian schools like that

of Israel Gelfand.

They were consciously developing infinite-dimensional representations

for the purpose of understanding quantum theory. And they bothered

themselves to what extent they could use Hermann Weyl’s work on compact

groups but now extending them to non-compact groups. So,

Harish-Chandra’s work is naturally a combination of Hermann Weyl’s work

plus the influence of the people in physics at the Princeton school, and

then the Russian School. He built his work by combination of these two

ideas.

He also had to do a lot of analysis and he based a lot of that on the

work of Laurent Schwarz – the Schwarz distributions. That was kind of

the analytical basis. So all these were new at the time and he was using

them. He was a very technical expert who was able to prove theorems.

But he was a bit of a machine: he turned out papers exactly thirty-three

pages long.

Yeah, exactly thirty-three pages!

He would say, “I assume you have read all of my six previous papers,”

and carried on. Which meant that only the very very devoted followers

would read it. And so his papers had these drawbacks. He was very, very

mechanical, he was very thorough, very detailed, coming up with very

good results. He had a big influence on people using bits of it. But I

think it was too formal a way to do it. I myself recently got interested

in this and worked with Wilfried Schmid. He was at Harvard, and we

redid some of Harish-Chandra’s work and I have recently come to

understand the physics better. So I think Harish-Chandra’s work will be

re-done from a modern point of view.

Do you mean to say that doing mathematics is more intuitive,

but when one writes papers, that’s not exactly the way one should

present it?

Well, you shouldn’t do it. In the old days, they did write like that.

Then it became more formalised. If you go back and read mathematics

written over a hundred and twenty years ago, it was not so formalised.

People gave you their ideas and then they give you some details. But in

more modern periods, this was not very formally correct. But they’re

wrong: it was correct at the time. I think the fundamental insights of

mathematics are by intuition and insight, and with examples making sure

you are right. The details on proof – they are a function of time. As

years went by, the nature of proofs changed, they evolved to become more

formalised. Too much so. Now it is a bit too formalised. That was part

of the influence of Nicolas Bourbaki.

Exactly! I was going to come to that. I remember reading

somewhere that Harish-Chandra was considered for the Fields Medal in

1958 but a forceful member in the committee thought that

Harish-Chandra’s style was Bourbaki. I think it was Rene Thom who got

the Fields Medal that year, in 1958.

In Edinburgh. I was here at the time. Hodge presided over that

congress. I was young and had to help people move rooms and that sort of

thing. Now, the story about Bourbaki is that Bourbaki was sort of made

up of a reforming group of French mathematicians in the post

First-World-War period. They were trying to restructure French

mathematics.

They started around… well, structures. They wanted to emphasise the

importance of structure. All the words we use today – like isomorphism –

come from Bourbaki. But at the end of the day, the abstract notions and

ideas, they were the good parts. The bad parts were that they then

wanted to make proofs, because the previous era had been full of the

Italian algebraic geometers who had no foundations. Bourbaki wanted to

have very rigorous foundations. In this direction, they went too far. So

they were a good influence and a bad influence.

They worked together because the original guys who founded Bourbaki,

they knew what they were doing, and they could do both together. The

next generation, who weren’t the founders, they only inherited the

formal part. So they went off in a totally wrong direction.

The tragedy of mathematics with Bourbaki was that they were very

successful in their fundamentals but they were over-enthusiastic, or

their supporters were over-enthusiastic, and that led to the bad

reputation of Bourbaki. And so, in that sense, Harish-Chandra was not

formally a member of Bourbaki, but he grew up under the influence of

Bourbaki and the rigorous style of writing. And so, I’m sure his work

will be taken apart and redone in a totally different way with an

emphasis on ideas.

I’m now trying to understand things. I think I’m understanding a lot

of things [now] that I didn’t understand when I was younger. I

understood partially [then]. You know, understanding is a slow process.

You evolve. As you get nearer and nearer to dying, you understand the

world better and better. And finally when you get out there you go “Ah!

It’s all obvious.” [

Laughs]

So would you say that earlier, mathematics was in some sense

driven by application and in the 20th century, mathematics developed for

its own sake and not necessarily for its application?

That was always like that, for its own sake. When the Greeks did mathematics, it was always done for its own sake.

But perhaps the sophistication became more pronounced in 20th century, in some sense.

Well, up and down. In the medieval period, people did it for the

glory of god. You built cathedrals for the glory of god. You built

mathematical theorems for the glory of god. Whatever you call it, you do

it for its own sake. You weren’t building cathedrals as houses for the

people. Somebody else built houses for the people. You built cathedrals.

Mathematicians basically build cathedrals. Cathedrals are big works of

intellectual architecture with theories. And they were built because

they were beautiful, because you like beauty. Beauty was motivating. You

try to build a building without an idea of beauty, you will build a

concrete tower. It may be very good for standing a fort or a castle but

it is not inspiring.

The Greeks – Euclid, Pythagoras – did it for its own sake. The Arab

world did it for the glory of Mohammad. The Indians and Chinese all did

it for its own sake in their own language. They would refer to their own

gods or their culture or their beauty.

Bertrand Russell made a very provocative remark about Pythagoras.

Bertrand Russell was, interestingly enough, the only mathematician to

get the Nobel Prize for literature. He said that Pythagoras was the most

important person who ever lived. Why? Because he made two fundamental

discoveries. One was that numbers were at the heart of music – the tonal

scales.

//You strive to truth but beauty is your guide. Beauty is the torch that lights the path//

The mathematical basis of musical verses were known before that, but

Pythagoras was the first person who realised the special significance

that numbers have. Secondly, he realised the real of importance of the

Pythagoras Theorem. Everybody knew Pythagoras’ theorem well before

Pythagoras but what Pythagoras emphasised was that you could have

Pythagorean right-angled triangles with rational sides.

So the two most important things in the world – music, a part of our

culture and geometry, a part of our agriculture and the utilitarian

world – both of these things depend on numbers. So this means that the

world is rational because it is built on numbers. We don’t need to have

mysterious gods, we don’t need to pray to the gods for it to rain. We

can appeal to rationality. That was the beginning of modern science.

In other words, what Pythagoras said, according to Russell, was that

there are laws of nature. It is our job to find out the laws of nature.

That’s what scientists do. The laws of nature… well, we don’t know who

created them. But we believe there are laws of nature. And that’s a

faith. But then you can work in this field but still be motivated by the

beauty of nature. And that is what all of them believed: they believed

they worked to enhance the glory of god. The beauty was the driving

force; it always has been.

So mathematics has always been developed two ways. First, not for

utilitarian purposes but for beauty. Secondly, for utilitarian purposes

because you had to do engineering. So it was always these two strands.

And Pythagoras realised that. Individual mathematicians are motivated by

the beauty of mathematics, but they also have to make sure that the

foundations were correct. If a bridge is collapsed, you build a new

bridge. So you have to balance between beautiful theory and a theory

that works. But a theory that has no beauty will never work.<>

That’s a beautiful quote!

Hermann Weyl has a beautiful quotation that I like to use a lot. He

said “All my life, I pursued two objectives: truth and beauty. But, when

in doubt, I have always chosen beauty.” I like this quotation because

if you are a mathematician, you think surely truth is more important.

But Weyl’s dictum can be explained in the following way. Beauty is

something you see here. I see something – say, that tree is beautiful.

You can’t deny me my view because I feel it here, emotionally. If I say

something is true, that is, I apply my logical reasoning, I’m never

quite sure I’m right because the nature of proof changes with time. What

is accepted now, what you may have, is a perception of truth. Truth is

something you never reach. Truth is the ultimate god. You strive to

truth but beauty is your guide. Beauty is the torch that lights the

path.

So you have both truth and beauty but truth you never reach. Beauty

you have here, now. So if you are in doubt, you see a mountain, and you

ask “Should I go this way or that way?” Beauty would tell me to

go that way. And usually, it is a correct guess. But you’ve got a choice

to make. Do you choose the formalistic engineering approach or do you

choose the beautiful approach? And most of the time our heart says

“beautiful” and the heart will be right. So it’s a very subtle thing.

Hermann Weyl said it very explicitly several times and I believe in that

strongly.

I personally admire Hermann Weyl because he defined what a manifold is as we know today.

Of course, the idea was around that time. But he was the first person to formally define it.

Because even Élie Cartan himself says at one point that it is difficult to define what a manifold is.

Hermann Weyl was a master of ideas. I’m an enormous admirer.

Interestingly enough, when I wrote that obituary, I said I am going to

focus on the influence he had but I never focussed on the parts of

mathematics that I don’t understand. The two parts I said nothing about

were his very great concern with the foundational questions of

mathematics – big arguments with David Hilbert and Gödel, which he was

very much involved with. I never paid much attention to logical

foundations so it’s not for me.

And the other thing that I said I wouldn’t do anything about was

this: he had some very interesting questions in bits of number theory

that I didn’t know much about. I mean, I did know some number theory,

but he obviously went into much greater depth, such as with Diophantine

approximations. In the last ten years, I got interested in both these

things of Hermann Weyl. I realised what he was trying to do about the

logical foundations of mathematics and in number theory.

I can write now another interesting addition to that obituary. That

would be another excuse for bringing it up to date. I always thought I

would follow in Hermann Weyl’s footsteps and I was following them only

in the areas I knew, but now I’m following them in the areas I didn’t

know. And I’m still following Hermann Weyl. He is my spiritual beacon.

And I’m still trying slowly to catch up with him. My only regret is that

I didn’t meet him. He was sixty years ahead.

But I heard him talk at the Amsterdam Congress [ICM]. He was the

president of the Fields Medal committee that year and he had to give big

speeches about the Fields medallists. The two Fields medallists at the

time were people I knew very well: Jean-Pierre Serre and Kunihiko

Kodaira. They were different characters, although for a while their

interests overlapped. And Hermann Weyl’s talk was a very magnificent

speech. First he talked about Kodaira because Kodaira was working in the

things that Hermann Weyl studied at great length: differential

equations and tensor harmonic forms. Weyl brought Kodaira from Japan,

where he was working alone. Kodaira was his Weyl’s protégé. Serre he

didn’t know. He poetically concluded his speech with the following

remarks:

Here ends my report. If I omitted essential

parts or misrepresented others, I ask for your pardon, Dr. Serre and

Dr. Kodaira; it is not easy for an older man to follow your striding

paces. Dear Kodaira: Your work has more than one connection with what I

tried to do in my younger years; but you reached heights of which I

never dreamt. Since you came to Princeton in 1949 it has been one of the

greatest joys of my life to watch your mathematical development. I have

no such close personal relation to you, Dr. Serre, and your research;

but let me say this that never before have I witnessed such a brilliant

ascension of a star in the mathematical sky as yours. The mathematical

community is proud of the work you both have done. It shows that the old

gnarled tree of mathematics is still full of sap and life. Carry on as

you began!

He wrote this book about the classical groups.

4 It

is a marvellous book written in response to an attack. In the old days,

people did invariant theories and when Hermann Weyl wrote this book,

people said “Oh, a Hermann Weyl book. He says all this formal nonsense.

He doesn’t understand any invariant theory. We old guys, we do invariant

theory.”

Hermann Weyl was so cross. He did understand invariant theory much

better than anybody else. So he wrote this book as a response just to

show that he did understand it. And he wrote a beautiful book; it’s a

book you read many, many times. There are so many things that it isn’t a

single-track book. As opposed to the book written around the same time

by Claude Chevalley on Lie groups. Single track – you follow the axioms

and you end. By the time you finish, you know all of it and you throw

the book away and never look at it again. Hermann Weyl’s book was the

contrary – you read it and you reread it. Every time you get some new

insights. I’ve done that myself. So it’s a fantastic book.

That’s very interesting, what you said. Again it brings me

back to Harish-Chandra. I think he was quite influenced by Chevalley in

Columbia. He heard his lectures and there is this wonderful recollection

by George Mostow. Apparently, Chevalley’s lectures were very planned,

very well laid out and everything. And at one place, Chevalley kind of

stopped and sort of went to a corner of the board, wrote something and

covering that part of the board…

Yeah, I’ve heard that story too. He drew a picture.

[

Laughs]

And then he said “My assertion is certainly

correct, but I don’t see at the moment how to prove it.” Apparently,

Harish-Chandra later remarked to Mostow: “How can one know a

mathematical statement is true without knowing how to prove it?”

Both of them were true. I think the point is that Chevalley, when he

wrote books about algebraic geometry, people said to him – this is

another story – “When you think of an algebraic curve, what do you think

about?” He wrote in the corner “

f(

x,

y) = 0″ [

laughs].

Then he rubbed it out you see. To hide the fact that… I mean, these

stories were all aspects of the truth. I think Harish-Chandra is more

like Chevalley than Hermann Weyl by a long shot. He was more fastidious

about proofs but Chevalley probably had the proofs – maybe he wrote a

bit too fast. Chevalley was a bit older.

Michael

Atiyah (centre) and I.M. Singer (left) receiving the Abel Prize in 2004

courtesy Scanpix/The Norwegian Academy of Sciences and Letters

How is a physicist’s approach to mathematical truth different from that of a pure mathematician?

That’s a very interesting question. I can’t answer it in two

sentences because my ideas are quite subtle on that. I’ll give you a

quick summary.

First of all, there is no one class of physicists. Physicists are a big spectrum – appropriate terminology [

laughs].

So one end you get physicists who are only interested in having some

kind of a crude model which will fit with experiment up to the accuracy

they’re concerned with.

They are not like engineers, but they’re like an engineer with some

understanding. They understand the mathematics… well, some of them

bother. Some are just engineers who want a formula which works. Some

will say that the formalism or the mapping breaks down and I don’t know

what to do. An engineer whom the formula comes from will give it to a

physicist, who is a little bit of a mathematician who understands it.

But then it keeps shifting.

So you move further along this line, and eventually, you will end up

at the far end with the physicist who says, “I want to understand

everything. All of it. I want to understand gravitation,

electromagnetism. I want a theory that is completely universally

perfect.” They’re at the extreme wing. By the time you get to the

extreme wing, you have outflanked the mathematicians. The mathematicians

are somewhere in the middle.

Now, “everything” means physics at all scales – big, small,

classical, quantum. I think mathematicians are in between with a shorter

range. They are influenced by applied mathematics and engineering. They

know they have to find technical tools, so they have something in

common with engineers. The engineers and the applied mathematicians are

much the same. Then the mathematicians develop mathematics but more for

the sake of following the beauty. So mathematics is much more diverse

and it also has many more applications.

Physicists are focussed on, well, they call it the theory of

everything, but they’re really meaning fundamental physics. The

mathematicians are more diverse and there are more schools of thought.

Then, as you go further up, mathematicians are interested in more

advanced physics, quantum theory and so on. They have to follow the

physicists, keeping track with the physicists. Their mathematical models

have to fit the physical theory upto some point.

But then the question is how far on the scale do you want the

physical theory to work. I think in this way you get towards the extreme

end of the realm of the mathematicians who are logicians, the

fundamentalists like Gödel, Turing and Hermann Weyl, all who are

concerned with the logical foundations of mathematics. The questions

they are asking seem to be demanding answers of a fundamental nature

that in the real world doesn’t arise.

The physicists are interested in the foundations in their own

language. They don’t really want to worry about the logical foundations

like the mathematicians. They want to worry about the formal

mathematical foundations for their own purposes. So they are kind of

weaker fundamentalists; they are fundamentalists of a different kind

still. They are really separated from the logicians. There are a few

people trying to cross the border, but very few of them.

You can differentiate different physicists based on the scale they

operate. Are you only concerned with the nucleus and the atom? Are you

interested in molecules? Are you interested in galaxies? Are you

concerned with the universe? What happened before the Big Bang? You can

keep increasing the scale, and you get into deeper and deeper waters.

Mathematicians down here are also struggling.

There are some people trying to bridge the gap. Gödel was interested

in physics, and you’ve heard of John Conway. But they are rather scarce

in number. No division is clear cut but broadly speaking I see a tree

which starts with engineering and goes along with physics and

mathematics in parallel, with a few ups and downs, but later on going

off into… like a river delta valley. It’s rather strong… a big

mainstream here and there, with a few rivers in between. That’s not a

bad analogy.

I am somewhere… I think I climbed a little hill and am looking down

on this lot trying to get a good view. If you are too high up, you can

only see a single line. If you are too low down, you see too much

detail. You’ve got to be just right. And probably best if you are in a

balloon going up and down. So you change your view depending on your

perspective. If you are higher up, you see different scales. If you want

to see a mouse, you come down closer to the earth.

Could one describe this as two sides of a coin? For example, in mathematics, the two sides can be algebra and analysis.

I don’t think I accept your distinction. My distinction would be

algebra and geometry. Analysis is more across the border. In analysis,

you worry about the continuum in geometry. Analysis in algebra is when

you go, for example, from polynomials to analytic functions. Analysis is

a bridge that connects algebra and geometry. And algebra has old

traditions in India and so on, and geometry has an old tradition with

Pythagoras and the Greeks.

Analysis is common ground. And of course, the physicists grow out of

this. Algebra and geometry connected by analysis is a good bridge. Then

you follow that through to physics. Algebra leads to some formal

computation, geometry leads to insights – Dirac lives here and [Abdus]

Salam lives there. Of course, which is up and which is down is… [

laughs] I would put them on a plane so that we are not distinguishing.

Algebra leads to analysis immediately once you start, for example, to

consider infinitely many things. Finite algebra is finite. Finite

geometry is very finite. But things only get interesting when you allow

infinite things. Infinite series, decimal approximations of numbers,

continuum limits, differential calculus – how do you define the

derivative? As soon as it becomes infinite – and of course, it can be

infinite in different degrees – how big is your infinity? And in this

whole scale, how big is infinity? What is infinity? There is more than

one infinity. You can write twenty five books about infinity [

laughs]. But that is a story for another time.

It has been a great honour and a pleasure talking to you.

I always like talking. It is one of my weaknesses.

It was really delightful.

This interview was conducted by C.S. Aravinda. It was originally published by Bhāvanā

magazine and has been reproduced here with written permission. Read the original here.