Berna Gomez, wearing glasses to test the prosthesis. (John A. Moran Eye Center at the University of Utah)

Brain Implant Gives Blind Woman Artificial Vision in Scientific First

A 'visual prosthesis' implanted directly into the brain has allowed a

blind woman to perceive two-dimensional shapes and letters for the

first time in 16 years.

The US researchers behind this phenomenal

advance in optical prostheses have recently published the results of

their experiments, presenting findings that could help revolutionize the

way we help those without sight see again.

At age 42, Berna Gomez developed toxic optic neuropathy, a deleterious medical condition that rapidly destroyed the optic nerves connecting her eyes to her brain.

In

just a few days, the faces of Gomez' two children and her husband had

faded into darkness, and her career as a science teacher had come to an

unexpected end.

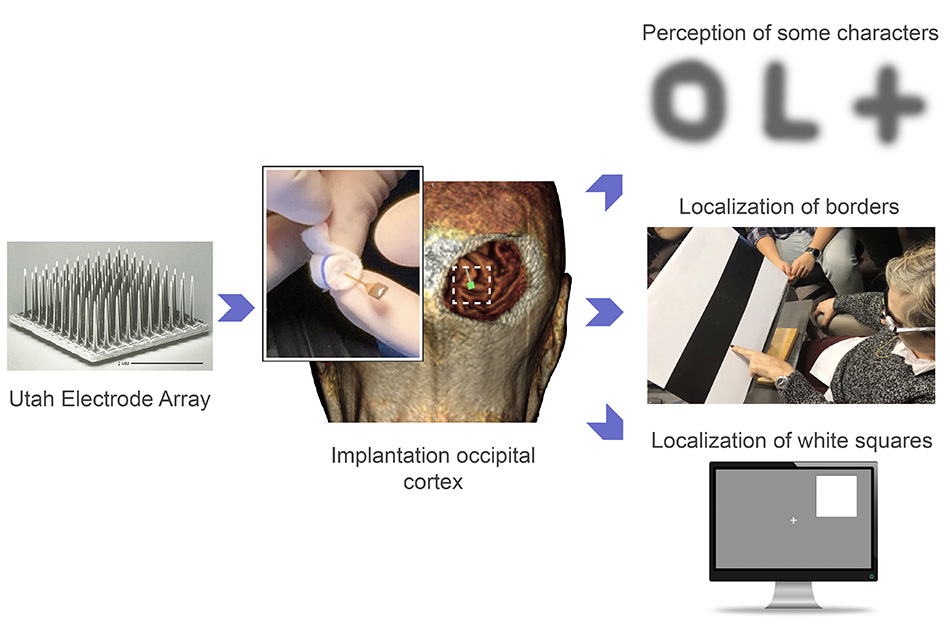

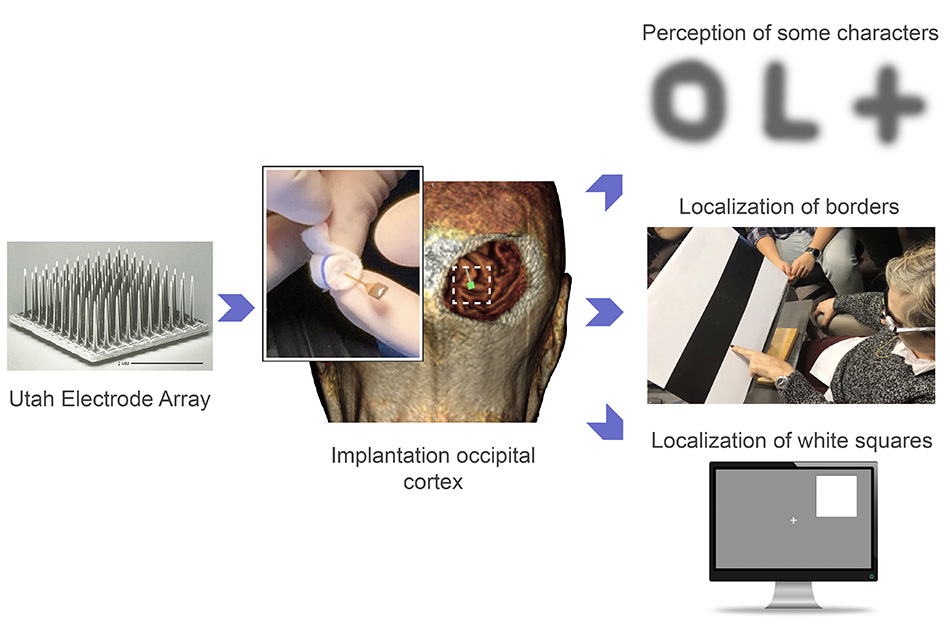

Then, in 2018, at age 57, Gomez made a brave

decision. She volunteered to be the very first person to have a tiny

electrode with a hundred microneedles implanted into the visual region

of her brain. The prototype would be no larger than a penny, roughly 4

mm by 4 mm, and it would be taken out again after six months.

Unlike retinal implants, which are being explored as means of artificially using light to stimulate the nerves leaving the retina,

this particular device, known as the Moran|Cortivis Prosthesis,

bypasses the eye and optic nerve completely and goes straight to the

source of visual perception.

After undergoing neurosurgery to

implant the device in Spain, Gomez spent the next six months going into

the lab every day for four hours to undergo tests and training with the

new prosthesis.

The first two months were largely spent getting Gomez to

differentiate between the spontaneous pinpricks of light she still

occasionally sees in her mind, and the spots of light that were induced

by direct stimulation of her prosthesis.

Once she could do this, researchers could start presenting her with actual visual challenges.

When

an electrode in her prosthesis was stimulated, Gomez reported 'seeing' a

prick of light, known as a phosphene. Depending on the strength of the

stimulation, the spot of light could be brighter or more faded, a white

color or more of a sepia tone.

When more than two electrodes were

simultaneously stimulated, Gomez found it easier to perceive the spots

of light. Some stimulation patterns looked like closely spaced dots,

while others were more like horizontal lines.

"I can see something!" Gomez exclaimed upon glimpsing a white line in her brain in 2018.

Vertical

lines were the hardest for researchers to induce, but by the end of

training Gomez was able to correctly discriminate between horizontal and

vertical patterns with an accuracy of 100 percent.

The Utah Electrode Array in action. (John A. Moran Eye Center at the University of Utah)

The Utah Electrode Array in action. (John A. Moran Eye Center at the University of Utah)

"Furthermore,

the subject reported that the percepts had more elongated shapes when

we increased the distance between the stimulating electrodes," the

authors write in their paper.

"This

suggests that the phosphene's size and appearance is not only a

function of the number of electrodes being stimulated, but also of their

spatial distribution… "

Given these promising results, the very last month of the

experiment was used to investigate whether Gomez could 'see' letters

with her prosthesis.

When up to 16 electrodes were simultaneously

stimulated in different patterns, Gomez could reliably identify some

letters like I, L, C, V and O. She could even differentiate between an

uppercase O and a lowercase o.

The patterns of stimulation needed

for the rest of the alphabet are still unknown, but the findings suggest

the way we stimulate neurons with electrodes in the brain can create

two-dimensional images.

The last part of the experiment involved

Gomez wearing special glasses that were embedded with a miniature video

camera. This camera scanned objects in front of her and then stimulated

different combinations of electrodes in her brain via the prosthesis,

thereby creating simple visual images.

The glasses ultimately

allowed Gomez to discriminate between the contrasting borders of black

and white bars on cardboard. She could even find the location of a large

white square on either the left or right half of a computer screen. The

more Gomez practiced, the faster she got.

The results are encouraging, but they only exist for a single

subject over the course of six months. Before this prototype becomes

available for clinical use it will need to be tested among many more

patients for much longer periods of time.

Other studies have

implanted the same microelectrode arrays, known as Utah Electrode

Arrays, into other parts of the brain to help control artificial

limbs, so we know they're safe in at least the short term. But it's

still early days for the tech, which risks a steady drop in functionality over just a few months of operation.

While

engineers beef up the reliability of the devices, we still need to know

exactly how to program the software that interprets the visual input.

Last year, researchers at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston inserted a similar device

into a deeper part of the visual cortex. Among five study participants,

three of whom were sighted and two of whom were blind, the team found

the device helped blind people trace the shapes of simple letters like

W, S, and Z.

In Gomez's case, there was no evidence of the device

triggering neural death, epileptic seizures, or other negative side

effects, which is a good sign, and suggests microstimulation can be

safely used to restore functional vision, even among those who have

suffered irreversible damage to their retinas or optic nerves.

"One goal of this research is to give a blind person more mobility," says bioengineer Richard Normann from the University of Utah.

"It

could allow them to identify a person, doorways, or cars easily. It

could increase independence and safety. That's what we're working

toward."

Right now, it seems only a very rudimentary form of sight

can be returned with visual prostheses, but the more we study the brain

and these devices among blind and sighted people, the better we will

get at figuring out how certain patterns of stimulation can reproduce

more complex visual images.

Perhaps one day, other patients in the

future will be able to trace the whole alphabet with this prosthesis

because of what Gomez has done. Four more patients are already lined up

to try out the device.

"I know I am blind, that I will always be blind," Gomez said in a statement a few years ago.

"But I felt like I could do something to help people in the future. I still feel that way."

Gomez's name is listed as co-author on the paper for all her insight and hard work.

The study was published in the Journal of Clinical Investigation.